This Nonprofit Acts Like a Tech Startup. Why Don't More Nonprofits Do the Same? Instead of constantly fundraising, Y Combinator graduate Watsi has adopted a more defined model.

By Laura Entis

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

When it comes to using technology to solve humanity's problems, so much more can be done. That's how Chase Adam feels about it anyway.

"It's crazy that there are huge engineering teams figuring out how we can add a different filter to our photos, but there are so few people using the Internet and technology to bring education or health care to the world," he says. "It's absolutely mind-boggling to me."

As the founder of Watsi, a nonprofit that allows people to donate small amounts of money to crowdfund medical treatments for individuals in 20 developing countries, Adam, 29, is doing his part to remedy this imbalance. While Watsi's mission is stereotypically nonprofit (in the best possible way), the company operates more like a technology startup.

Case in point: Today, Watsi announced it has raised $3.5 million in donations the same way a photo-filter app might reveal the close of its Series A round. In lieu of investors, Watsi's press release listed philanthropists and foundations, although some of the names– notably Y Combinator founder Paul Graham and venture capitalist Vinod Khosla – simply strengthened the analogy. As did the release's focus on growth metrics (since 2013 "Watsi has grown 20x, funding health care for more than 5,000 patients") and big-name hires ("the nonprofit has already recruited engineers from NASA, Microsoft and Palantir").

These similarities are no accident, says Adam. Technology companies, by nature of the competitive for-profit market, are efficient at raising money. Instead of adopting the traditional nonprofit fundraising model – i.e. constant fundraising – Watsi imitated the startup funding model, which allowed the company to ask for a set amount for a specific goal. Now it can focus entirely on doing the actual work of funding low-cost, high-impact medical procedures.

This logic neatly encapsulates Adam's working philosophy, namely take Silicon Valley's technology-steeped approach to work flow but use it to improve or save hundreds of thousands of lives instead of building the next pizza-delivery app.

"We have a rule at Watsi that at least half of our team is able to code," says Adam. The 11-employee nonprofit recently hired three engineers, and will use a large percentage of the $3.5 million to hire a few more. Together, they'll work on building and refining Watsi's operations. There is a lot to be done.

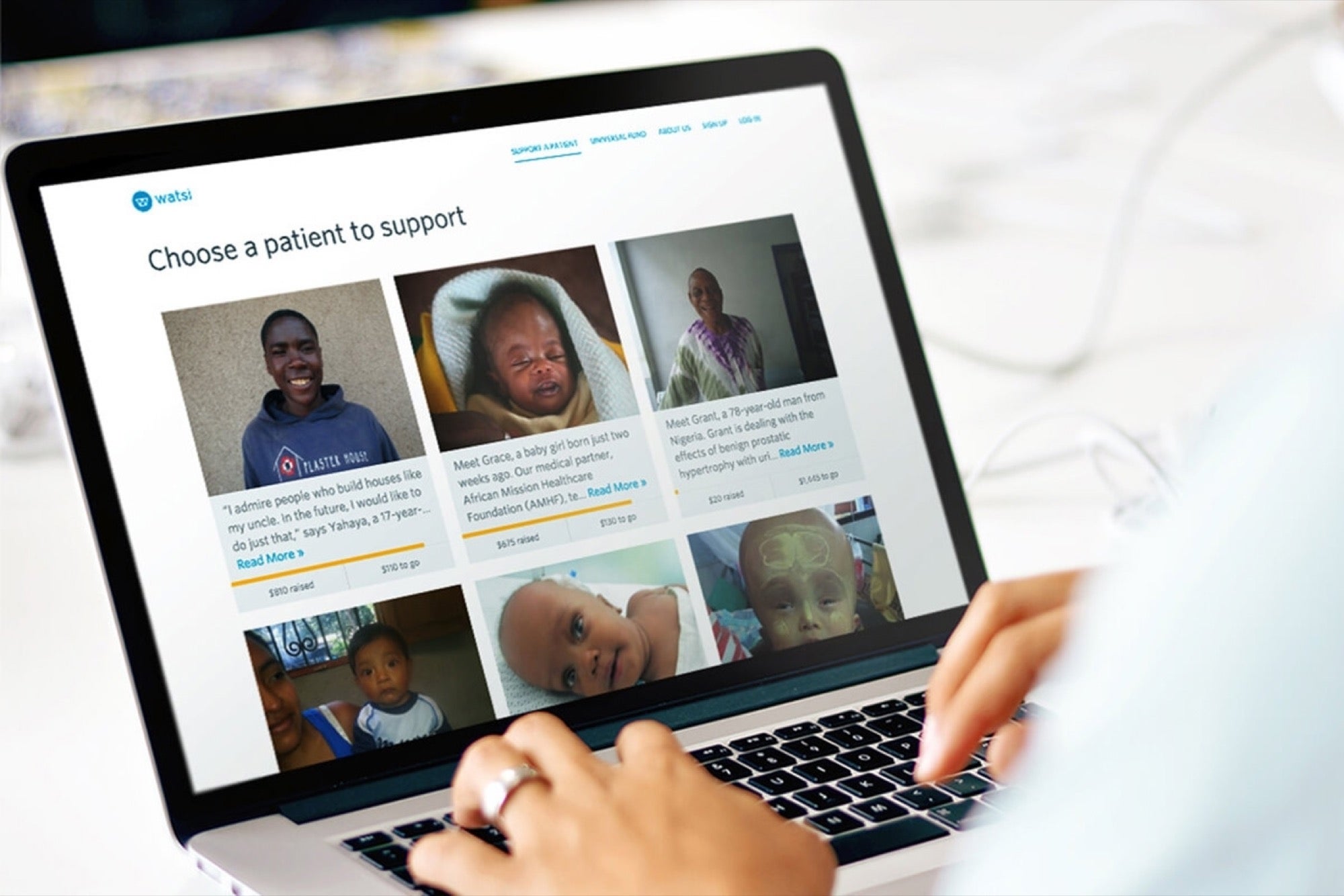

Watsi's site includes patient profiles and visitors can donate to fund individual people and procedures. The layout is clean and relatively easy-to-follow, but Adam isn't satisfied with the user experience. The real technology problems, however, occur on the back-end. Watsi's engineers are building a platform that enables its care providers to upload and manage patient information. "These people have varying degrees of technical literacy – we need to make a system that is simple enough for everyone from a nurse in Haiti to a doctor in Cambodia to use."

In a similar vein, Watsi is working to streamline how its health-care procedures are measured and the results communicated to donors. "Health care is complicated," says Adam. "Often times, it's degrees of success." Creating a uniform system and timeline for rating procedures will speed up and improve the organization's ability to determine an outcome. It will also help Watsi perform ongoing due diligence. A structured bank of health-care data allows Watsi to identify potential problems as they occur. If the standard treatment timeline for a medical condition is three weeks and a patient's progress isn't lining up with that average, the system should automatically flag the case for manual investigation.

These are sophisticated problems. To solve them, Adam needs top-shelf engineers. Eventually, this means paying market rate salaries – and engineers in Silicon Valley are expensive. Donors will soon discover exactly how expensive, as Watsi has taken the concept of "radical transparency," another Silicon Valley buzzword, to heart.

Related: Pencils of Promise Is Giving Nonprofits a Hard-Nosed Entrepreneurial Facelift

Watsi's website includes a Google Doc that lists its monthly financial statement, including administrative costs, salaries and travel expenses (Adam makes $65,000 a year, for the record). While he emphasizes that 100 percent of money donated through the site is spent to fund medical procedures -- salaries and additional expenses are covered by the nonprofits latest $3.5 million funding round – transparency is the default. As he begins to pay more for engineers, there is the possibility of pushback. But Adam is fairly confident that donors will realize that hiring the best people will result in the best software "which will help the most people in the end."

Adam would like to the non-profit sector take technology as seriously as he does. The Internet, by his estimation, "is the best tool we've ever developed as humans," and while most for-profit startups realize this, "the nonprofits that are solving some of the most important problems in the world – that are trying to save lives and provide education – are not adopting it fast enough. It's insane to me."

He's not necessarily blaming traditional nonprofits. "If you've been operating non-technically for 20 years, how do you incorporate technology in an effective way? You can't just sprinkle it on top," he says. "You have to change how you think about problems and how you solve them."

More encouragingly, he's noticed a new wave of nonprofits where the technology is baked into their DNA. In 2013, Watsi became the first nonprofit accepted to Y Combinator. Since then, a steady stream of nonprofits have graduated from the tech accelerator.

Adam's suspicion is that "it's becoming trendy to do a tech nonprofit." It's also his hope. "Man, if we could get more really smart MIT computer science graduates to try and fix education and health-care and poverty instead of building another photo-sharing app, that would be a good thing for the world."