These 2 Graphs Explain the Retail 'Apocalypse' Brick-and-mortar stores can't beat the convenience of online shopping, and they shouldn't try. Customers come through their doors for something else.

By Mike Mallazzo Edited by Dan Bova

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Long dismissed as "truthful hyperbole," the mass extinction of many American brick-and-mortar stores is underway. Payless is closing hundreds of locations as it files for bankruptcy, once white-hot Michael Kors is struggling, and Bebe is sunsetting its physical business entirely to focus on online sales.

Nationwide, shopping malls are closing at an alarming rate and providing AMC with an abundance of landscape shots for "The Walking Dead." Malls are so barren, owners have received numerous proposals to convert them into affordable-housing complexes. The first such units rent in Rhode Island for $550 per month. Are you listening, San Francisco?

While Amazon stock has netted a cool 350 percent return over the last five years, iconic American retailers in serious danger of fading into irrelevancy. The decline is rooted in a myriad of factors, but the existential threat to large retailers boils down to two, simple graphs.

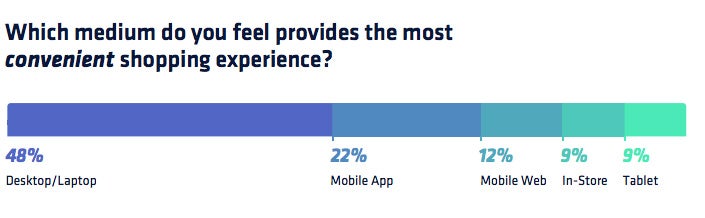

1. A crisis of (in)convenience.

According to a Dynamic Yield survey of 500 shoppers, fewer than 1 in 10 consumers believes shopping in-store is the most convenient approach. This hardly is surprising, but it must be examined as a major driver of brick and mortar's decline. Humans will gravitate toward the easiest method of commerce. Taking hours out of one's day to shop in-store doesn't fit the bill.

But brick-and-mortar stores never were going to win the battle for the most convenient shopping experience. Once economies of scale reduced delivery costs to mere trivialities, online shopping became the rational choice. As a test, our team recently ordered several bags of coffee for our eighth-floor office. The Amazon delivery arrived 23 minutes after we clicked submit.

Mobile shopping's rise has expedited physical stores' decline, true, but the die was cast long ago. The ubiquitous smartphone and emergence of product lines such as Amazon Dash merely are running up the score in a fixed game.

Related: Amazon's Whole Foods Deal Will Remake Strip Malls

No matter how innovative a retailer, in-store shopping harasses customers with basic miseries beyond the owner's control. The company CEO can't do a thing about the overzealous driver who saw your blinker but stole that parking spot anyway. The marketing director's creative campaign isn't worth much if the person in front of you at the register has 100 items, 50 coupons and three declined credit cards.

Brick-and-mortar stores can and should invest in basic convenience improvements, particularly those that unite online and offline channels. Again, this is a tough battle. Machines built to save shoppers' time often cause more problems than they solve. Self-checkout lanes are a perfect example.

There's a related threat in the graph above. Approximately 60 percent of the traffic on retail websites now comes from mobile devices, but only 16 percent of conversions take place on mobile. Smartphones' primary reason for existence is efficiency and convenience. Still, shoppers overwhelmingly prefer desktop devices, which see a smaller share of logins every day.

To stay afloat, retailers must optimize their mobile web and app offerings for convenience while optimizing the in-store experience around a certain je ne sais quoi that can't be found online. Sadly, many physical stores also struggle to find it.

Related: 4 Ways Brick-and-Mortar Stores Can Outsell Online Retailers

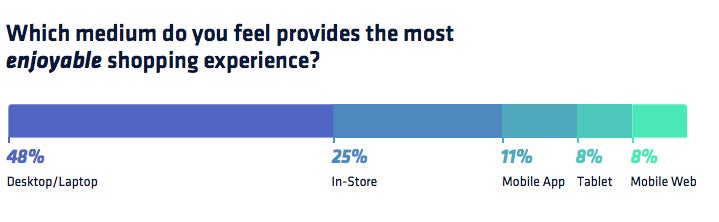

2. Make shopping fun again.

Shopping is a prime leisure activity for millions of Americans. Surely, then, the majority of shoppers must find brick-and-mortar stores to be the most enjoyable way to pass this time? The data suggests otherwise.

Think about stores whose aisles seem always full of customers. What do they have in common? They craft uniquely enjoyable experiences that cannot be replicated online. Shopping at Wegmans, IKEA and Costco isn't simply a means of acquiring stuff. These trips make up a legitimately enjoyable Saturday afternoon.

Related: You Sell Experiences Whether You Realize It or Not

Retailers go to great lengths to anticipate customer wants and provide thoughtful details. The effort is paying off. Wegmans' exciting in-store experience has led to roughly $8 billion in annual revenue, making it one of the largest private companies in the United States. Costco's share price has doubled in the last five years, and it's now the second-largest retailer in the world. Nearly 1 billion customers visited global IKEA locations last year (a boon for the suddenly blossoming lingonberry industry). Amazingly, IKEA's food sales brought in about $1.8 billion during the 2015 fiscal year ($1.6 billion euro at the time). That's more than Buffalo Wild Wings or Wendy's.

Even so, Wegmans provides the most powerful example of creating a memorable experience. The company competes against several unicorn startups it cannot possibly beat in convenience. Blue Apron and HelloFresh have found ways to cost-effectively deliver delicious, meals to your doorstep. Packing all the ingredients and preparation instructions in each bundle saves consumers hours at the grocery store. But Wegmans gives consumers a reason to want to spend hours at the grocery store. These strategies have led to such a strong cult following that New York City has heard months of buzz around a store that won't open until 2018.

This also is precisely where many of America's iconic retailers have failed. Most recent improvements to in-store shopping at large department stores have focused on beacons, heat maps or other self-serving tools for retailers that do little for the customer. The result? Shoppers experience an in-store visit that's not fundamentally different that it was two decades ago. (Hell, even the pop music piped through malls was better back then. Spice Girls, Radiohead and Third Eye Blind were dropping straight fire.)

Related: How 9 Successful Companies Keep Their Customers

Before Tony Hsieh founded Zappos, the idea of buying shoes online was unimaginable. Until it wasn't. Improving technologies mean there might never again be a purely utilitarian argument for visiting a store. From the moment retailers launched ecommerce sites, brick-and-mortar shopping was fated to decline as a basic necessity.

To stop the apocalypse, retailers must help consumers rediscover how in-person shopping can be a pleasure -- and create new benefits, perks and premiums to bring people through their doors.