Beijing’s Hutongs: Preserving History Through Business

These Chinese entrepreneurs sacrifice profits to maintain a piece of their culture.

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Special correspondent Joanne Yao, a freelance writer based in China, is reporting from Beijing throughout the Olympics.

The residents of Beijing have a talent for occupying separate realities even within a shared city. Stay long enough, and any visitor will realize that the capital city is unsure which era it belongs to.

At first glance, it appears as if the modern Beijing Olympic visitors are seeing is dominated by towering, neon-decked high-rises. More than 90 percent of the city’s estimated 17.5 million residents live in space-efficient apartments. Fewer than 10 percent go home to the hutongs–narrow networks full of open-air courtyard homes that originally housed the emperor’s most trusted and their families.

Although hutongs have existed for almost 600 years, as long as the Forbidden City, 82 percent of these iconic Beijing neighborhoods have been demolished since the early 1950s. Between 3,000 and 4,550 hutongs have weathered the Cultural Revolution and mass industrialization to survive in various states of dilapidation, according to the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage. Only 539 are protected as cultural and historical conservation sites.

Hutong, derived from a Mongolian word meaning “water well,” is the ancient Chinese equivalent of a neighborhood block. Beijing’s hutongs are lined with classic courtyard houses, called siheyuan. Translated as “garden with four sides,” these rooms of bamboo and stone are constructed around an open-air garden and have the distinction of being Beijing’s only single-lot homes. China’s immense population makes America’s house-and-backyard model impractical, so the overwhelming majority of Chinese live in homes that look exactly like apartments but are separately owned.

Hutong, derived from a Mongolian word meaning “water well,” is the ancient Chinese equivalent of a neighborhood block. Beijing’s hutongs are lined with classic courtyard houses, called siheyuan. Translated as “garden with four sides,” these rooms of bamboo and stone are constructed around an open-air garden and have the distinction of being Beijing’s only single-lot homes. China’s immense population makes America’s house-and-backyard model impractical, so the overwhelming majority of Chinese live in homes that look exactly like apartments but are separately owned.

Yet at a time when high-rises vastly outnumber courtyard homes, and Olympic construction destroyed an estimated 800 hutongs, staunch defenders have arisen from China’s entrepreneurial class to prove that these old Beijing neighborhoods are worth saving, even though China’s upwardly mobile prefer Western goods and new apartments to the hutongs their parents lived in.

Leaving Financial World Behind

Bobby Zhang, 36, worked in investment banking for more than eight years before opening Templeside Hutong Guest House with his wife in 2006. After spending two and a half years completing his studies in Australia, Zhang had tackled every obstacle to gaining a “golden collar” job as an investment banking manager–a position that would keep him and his family moneyed for life. After returning to China, Zhang felt his passion dissipating as his sense of morality clashed against career choice. The Chinese government had publicly dismantled an ex-employer as a corrupt organization while he was in Australia. He began noticing that other investment bankers, even colleagues, routinely cheated clients out of money and realized that the same was expected of him.

At the same time, his interests were changing. Zhang became fond of strolling in the hutongs, sometimes with these debates clouding his head. At his investment firm, he was leading research on the feasibility of budget hotel chains in China when he stumbled upon a hutong-based hotel that was charging $200-$300 a night. His boss decided against investing in the profitable market, so Zhang quit his job with one thought in mind: Why not create his own version of a hutong hotel? He would charge less, Zhang reasoned, so that anyone could afford a taste of this lifestyle.

At the same time, his interests were changing. Zhang became fond of strolling in the hutongs, sometimes with these debates clouding his head. At his investment firm, he was leading research on the feasibility of budget hotel chains in China when he stumbled upon a hutong-based hotel that was charging $200-$300 a night. His boss decided against investing in the profitable market, so Zhang quit his job with one thought in mind: Why not create his own version of a hutong hotel? He would charge less, Zhang reasoned, so that anyone could afford a taste of this lifestyle.

Many of his relatives and friends were shocked at what they felt was a waste of his degree and time. After all, what person would want to live in an old bamboo building when they could book a room with air conditioning and a private toilet?

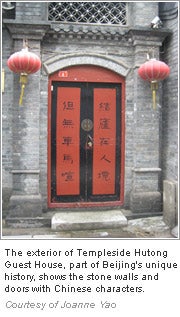

But Zhang approached his dream like a true professional. First, he wrote a business plan. Then he went through his network with a fine-toothed comb until he found “someone who knew someone” who owned a courtyard home and would lease it to him. In June 2006, he opened Templeside Hutong Guest House’s first location in Liu He Hutong, a stretch of hutong not protected as conservation site.

The area is like a step backwards in time. The few bamboo and stone courtyard homes on the lane grow lotus leaves on their rooftops, while shirtless neighbors cluster nearby, laughing and fanning themselves in the summer heat. Riding slowly up and down the narrow alley is a woman on a three-wheeled cart, calling out for recyclable glass bottles. And the question was answered: Although local Chinese usually take hutongs for granted, the lifestyle is very attractive to visiting foreigners who are intrigued by these culturally rich abodes.

The area is like a step backwards in time. The few bamboo and stone courtyard homes on the lane grow lotus leaves on their rooftops, while shirtless neighbors cluster nearby, laughing and fanning themselves in the summer heat. Riding slowly up and down the narrow alley is a woman on a three-wheeled cart, calling out for recyclable glass bottles. And the question was answered: Although local Chinese usually take hutongs for granted, the lifestyle is very attractive to visiting foreigners who are intrigued by these culturally rich abodes.

“My goal is simply to enjoy,” Zhang says, as his pet cricket chirps noisily from the window. He acknowledges that his business will never be large–after all, opening 100 Templeside Guest Houses would be missing the point. But life here is enchanting and fulfilling for the ambitious businessman.

The house, eight rooms with a capacity of 24, centers around an open-air garden corridor and a bamboo veranda, where Zhang and his staff of six teach guests how to make dumplings under the 300-year-old jujube tree. The serene view of peaked rooftops and nearby Beihai park is out of a storybook.

In April 2007, following the success of the first guest house, and an award for Best Hostel in China in 2007 by Hostels.com, Zhang opened a second location in An Ping Xiang, another nearby hutong area. This courtyard house had 10 rooms with a capacity of 20. Although tourism from the Olympics has allowed him to double the normal rates to $46 for a bunk in an eight-person room and triple them for a double-bed room with private bathroom and still fill up every space in the two houses, he anticipates the same revenue for 2008 as in 2007.

“Yes, the Olympics allow me to charge more for August, but because of visa problems, nobody came to stay here in June and July,” he says, unfazed. The combined revenues of the two guest houses reached $200,000 in 2007. His share surpassed what he could have expected to make in China’s investment banking industry.

A Home, With Guests

In another part of the city, Wang Hong Gang is sharing the hutong culture with a new generation of fiscally challenged travelers–the kind who trudge into a city with little more than what they can carry on their backs.

“You don’t need to come to Beijing to see skyscrapers,” Wang, 45, says without a hint of a joke on his tan face. “The government is only beginning to understand that visitors are attracted to China’s cultural heritage, and so are fascinated by hutongs.”

The avid backpacker and proprietor has never felt more carefree than in hutongs, where he spent his teen years eating dinner on his doorstep and playing card games with the neighbors from mid-day through lantern-lit nights. Wang, in jogging shoes and a Reebok T-shirt, looks like any other guest admiring the corridors of his 60-bed Beijing Downtown Backpackers Youth Hostel, which are plastered with “thank you” notes in every language.

The avid backpacker and proprietor has never felt more carefree than in hutongs, where he spent his teen years eating dinner on his doorstep and playing card games with the neighbors from mid-day through lantern-lit nights. Wang, in jogging shoes and a Reebok T-shirt, looks like any other guest admiring the corridors of his 60-bed Beijing Downtown Backpackers Youth Hostel, which are plastered with “thank you” notes in every language.

The two-story, 20-room hostel is the latest reincarnation of a Ming dynasty courtyard home, which also served as a printing factory during the Cultural Revolution. The property is part of Nanluogu alley, a very popular spot for international visitors and Chinese celebrities. A 2006 renovation remade the residential lane into a retail area of hip boutiques and coffee shops housed in traditional siheyuan. The profitable area belongs to the state, which holds many other hutongs sold by their owners for cash.

“We might be small, but we bring the comfort of home to travelers,” Wang says, comparing his hostel’s $9- to $17-a-night rates to large hotels (a typical four-star hotel in Beijing averages $150).

All eight staff members are locals but go home only two or three times a month–they live and dine at the hostel, with each other and a changing pool of affable visitors. At the core of the business is an earnest desire by owner and staff to replicate the camaraderie of Beijing’s hutong culture.

All eight staff members are locals but go home only two or three times a month–they live and dine at the hostel, with each other and a changing pool of affable visitors. At the core of the business is an earnest desire by owner and staff to replicate the camaraderie of Beijing’s hutong culture.

Even though Backpackers is completely booked even after increasing its rates six-fold, annual revenue will remain the same during this Olympic year due to tightened visa policies that created a housing surplus in the pre-Olympic months from April to June, balanced with Olympic profits in August. From January to March, the Chinese government reported a 2.6 percent increase in tourism, but April saw a decrease of 1.5 percent from 2007.

More alarmingly, a doubling of yearly rent in trendy Nanluogu alley has forced Wang to predict that his 2007 revenue of $300,000 will be cut in half in 2008, despite a full house and doubled rates. Although he is irritated by these unexplained increases, Wang sees his original intention clearly.

“The money in your purse is the motive for every hotel I’ve been to in China,” he says. “People don’t understand sometimes, but this is a home, of which our guests are a part, and not a landlord-to-tenant relationship based on money.”

Preserving History

More than anything, starting a hutong business is a labor of love mixed with a personal determination to share the beauty of the hutong’s dying ways–a lifestyle filled with conversations over shared meals, on a doorstep or in a courtyard under the stars. In a country that boasts thousands of years of history, only a few worry over preserving these living histories, perhaps because they are not yet lost.

The Olympics have not helped, and there are rumors that the government has told hostels to turn away foreign guests involved professionally with the Olympics, because they “should” be staying in five-star hotels.

However, growing domestic appreciation and foreign interest in the hutongs has become a surprisingly effective method for preserving these unprotected artifacts. Zhang and Wang both estimate that 90 percent of their visitors are foreigners who hear about their hostels through word of mouth or review-based booking sites such as Hostels.com, while the other 10 percent are domestic Chinese inclined towards art, music and literature.

The bustling crowds in Nanluogu alley and the hutong hostels’ fully-booked rooms show that the mystique of old Beijing culture is a powerful magnet for foreign capital and China’s small but growing creative class.

“I don’t think I am a successful businessman. I am pursuing a dream, and sharing with others,” Zhang reflects, a rare smile on his face.

Special correspondent Joanne Yao, a freelance writer based in China, is reporting from Beijing throughout the Olympics.

The residents of Beijing have a talent for occupying separate realities even within a shared city. Stay long enough, and any visitor will realize that the capital city is unsure which era it belongs to.

At first glance, it appears as if the modern Beijing Olympic visitors are seeing is dominated by towering, neon-decked high-rises. More than 90 percent of the city’s estimated 17.5 million residents live in space-efficient apartments. Fewer than 10 percent go home to the hutongs–narrow networks full of open-air courtyard homes that originally housed the emperor’s most trusted and their families.