Who Would Invest in Your Startup, and Why?

The type of funding you should pursue depends on your business’s value and scalability.

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

When we launched Cielo MedSolutions, a SaaS provider of population management healthcare apps, in 2006, my co-founder and I assumed we’d be able to raise venture capital. After all, we both had track records of having built and run software businesses and making money for investors. However, we failed to raise VC funds, and had to settle for a far more modest amount of capital from a combination of angels, economic development agencies, non-profits and federal grants. Partly as a consequence, we grew considerably more slowly than we had hoped. We ended up with a nice exit — sold to The Advisory Board Co. (ABCO) a little over four years later — so nobody’s feeling sorry for us. But, it wasn’t the big splash we set out to create.

Related: You Can’t Get VC Funding for Your Startup. Now, What?

Why? Even I, as a student of the game, have had trouble gauging startup investor interest.

This experience — combined with observing hundreds of other startups — motivated me to look more closely at these tough questions: As you’re thinking of launching a business, or looking to take your existing business to the next level, should you aspire to raise outside financing? And if so, what types of funding sources might consider your business to be an attractive investment? VCs? Angels? Friends and family? None of the above?

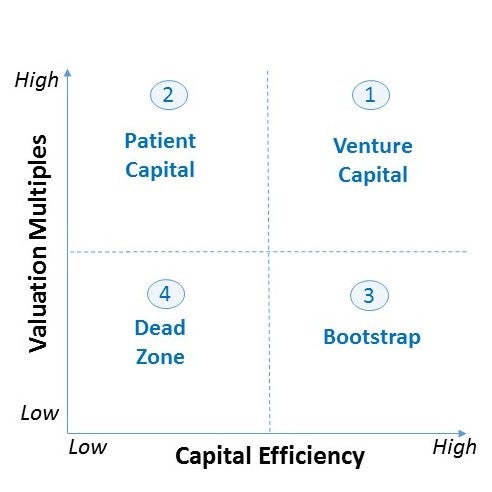

The Startup Fundability Matrix

In my recent book, The Launch Lens: 20 Questions Every Entrepreneur Should Ask, I introduced the Startup Fundability Matrix (see below), a conceptual framework that can provide you with preliminary answers to these questions.

Related: Is the VC Era Over? Let’s Hope So for the Sake of Business.

A quick, nerdy explanation

The x, or horizontal, axis of the Startup Fundability Matrix indicates capital efficiency (ranging from low to high). All other things being equal, outside investors prefer to put their money behind a business that’s capital efficient, meaning that for every dollar invested, it’s good at producing strong returns on a dollar-for-dollar basis. On this scale, the more “investable” businesses tend to be those that (a) require only a modest amount of capital to launch, and/or (b) can be scaled dramatically and efficiently by injecting just a modest amount of additional capital.

The y, or vertical, axis denotes valuation multiples (again, ranging from low to high). Valuation is the value of the company, or its overall financial worth to investors. Since early stage companies are privately held, and therefore don’t have a stock price you can look up on a public exchange, investors often use patterns from comparable companies to estimate the valuation of a startup. The most commonly used metric is the valuation multiple — that is, how much certain types of companies are typically worth, measured as a multiple of the last 12 months’ earnings (profit) or revenue (total sales). In general, businesses that achieve high valuation multiples are those that show three characteristics: high growth potential, sustainably high profitability and strong differentiation versus competitors.

So, now we’re ready to look at where various businesses fall in the Startup Fundability Matrix. Here are the four quadrants:

Quadrant 1 (upper right): Venture Capital — Businesses have a combination of high valuation multiples and high capital efficiency — inexpensive to launch and/or inexpensive to scale; these startups are the most attractive to VCs, corporate strategic investors and organized angel groups (which often behave like VCs).

Quadrant 2 (upper left): Patient Capital — These companies share the high valuation multiples with Quadrant 1 firms, but are less capital efficient, often because they lend themselves to less rapid scaling due to addressing a more modest market. These businesses tend to be better suited to investors who are more patient and perhaps less oriented toward pure financial returns — such as friends and family, specific angels with a special affinity for your particular sector, federal government grants, or state and local small-business loan programs.

Quadrant 3 (lower right): Bootstrap — These businesses rank relatively poorly on the scale of valuation multiples; on the other hand, they tend to be capital efficient (inexpensive to launch and scale). Think of Quadrant 3 firms as cash-flow or lifestyle businesses. It’s often possible to get such a business up and running with a modest investment out of savings or a bit of credit card debt.

Quadrant 4 (lower left): Dead Zone — Businesses here are extraordinarily hard for entrepreneurs to finance, and for good reason — they require a lot of capital to launch, and once up-and-running, are simply not that valuable. As a consequence, outside investors tend to run away from such startup ideas.

Related: 5 Ways to Bootstrap Your Vision Into Reality Without Outside Funding

How I could have used this tool

Circling back to Cielo MedSolutions, we launched the company assuming we were in Quadrant 1, an “investible deal” for VCs. We were wrong, because most healthcare IT-oriented VCs, while feeling comfortable with the high valuation multiples in our sector, suspected that we were too niche-y — addressing too modest a market — to be dramatically scalable post-launch. Although we didn’t have the benefit of the Startup Fundability Matrix at the time — and hindsight is 20:20 — what the VCs were effectively signaling to us is that we belonged in Quadrant 2.

We raised a couple of million dollars from a blend of “patient capital” investors. Had we known our “quadrant” up front, we could have saved a lot of time pitching VCs, and redirected our efforts toward selling to customers, building industry alliances and the like. Alternatively, this clarity of thought might have motivated us to explore broadening our product offering.

Related: 5 Common Mistakes That Keep Venture Capitalists From Investing

How you can use this tool

Applying the Startup Fundability Matrix to your startup can help you be clear-eyed about whether you should aspire to raise outside capital, and if so from what types of investors.

If you think you’re high on the y-axis (i.e., high valuation multiples), then the primary determinant of whether you’re in Quadrant 2 (Patient Capital) or 1 (VC) is market size. Narrow or niche product businesses push a company to the left (Quadrant 2), while very large addressable markets and broader product platforms tend to push a company to the right (Quadrant 1).

On the other hand, if your business ranks low on the y-axis (low multiples), the principle factor pushing you left or right on the x-axis is launch cost. Companies that can be launched with a modest amount of capital fall into Quadrant 3 (Bootstrap), while those that require large amounts of capital to build (e.g., to fund construction of a factory or a large store, and to purchase large amounts of inventory) fall into Quadrant 4 (Dead Zone).

At the earliest stages of company development, the Startup Fundability Matrix can even help you think through the pros and cons of different business models.

If, for instance, you’re an entrepreneur with a passion for buying and selling used musical instruments, a Quadrant 3 approach might be to open a brick-and-mortar store, with all its associated overhead and geographic constraints. Tough to get financed, so you’ll probably need to bootstrap it.

Alternatively, you could pursue a Quadrant 2 (or even possibly 1) business model and create a re-commerce marketplace where your website enables sellers/consigners of instruments to find interested buyers. By making that business model shift, you’re tying up less capital in a physical store and inventory, while broadening your geographic reach, profitability and scalability.

In this example, the latter business model may not only be more fundable, but stands a much better chance of being sustainably profitable, and eventually earning money for you while you sleep.

When we launched Cielo MedSolutions, a SaaS provider of population management healthcare apps, in 2006, my co-founder and I assumed we’d be able to raise venture capital. After all, we both had track records of having built and run software businesses and making money for investors. However, we failed to raise VC funds, and had to settle for a far more modest amount of capital from a combination of angels, economic development agencies, non-profits and federal grants. Partly as a consequence, we grew considerably more slowly than we had hoped. We ended up with a nice exit — sold to The Advisory Board Co. (ABCO) a little over four years later — so nobody’s feeling sorry for us. But, it wasn’t the big splash we set out to create.

Related: You Can’t Get VC Funding for Your Startup. Now, What?

Why? Even I, as a student of the game, have had trouble gauging startup investor interest.