Keeping Your Money Safe from Shady Advisors Don't be stunned when I tell you this. But, you can't trust every financial advisor out there. I mean there really are people out there like Matthew McConaughey's character in...

By Jeff Rose

This story originally appeared on Due

Don't be stunned when I tell you this. But, you can't trust every financial advisor out there. I mean there really are people out there like Matthew McConaughey's character in "The Wolf of Wall Street" conducting some really dirty business.

In fact, according to one study, 7.3% of financial advisors in the United States have been cited for abuse. If you dig deeper into the data, though, one in 12 financial advisors in the U.S. has been cited for misconduct.

"These things are not frivolous," Mark Egan, an assistant professor of finance at Harvard Business School and a co-author of the study, told Forbes. "The average settlement is in excess of $100,000 and the median is $40,000. These are costly offenses."

Unbelievable, right? The last thing that you would expect is that a financial advisor would embezzle money or get you wrapped up in a Ponzi Scheme. But, as far as I'm concerned, most of these financial planners are doing a good job. Not an amazing job. But, a decent enough job where they're not scamming their clients.

So, how can you find a trustworthy advisor from one who doesn't have your best interest at heart? Or, even worse, are straight-ups stealing from you?

The Fiduciary Duty

First things first. Let's talk about fiduciary duty.

"All financial advisors are held to a standard of care when dealing with investors," explains Robert Pearce, P.A. "Registered financial advisors have a higher fiduciary duty to their clients under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940."

The highest level of care must be provided by financial advisors, including making appropriate investments and providing relevant information to their clients.

"Knowing whether your financial advisor is registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or a state securities regulator is important because if the advisor breaches the fiduciary duty, you can bring a claim against the financial advisor through the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA)," adds.

The FINRA regulates advisors and their firms and assists advisors and investors to settle disputes.

What's Their Planning Approach

Moving on, here's one glaring red flag to be on the lookout for.

Imagine, for instance, that they make a recommendation to change something in your portfolio. But, you don't fully understand it. Are they doing so because they genuinely want you to increase your earning potential or decrease your risk level or diversify more? Or, is it because it will help them line their pockets more — which obviously doesn't benefit you.

While it's only fair that both you and the advisor make money, you don't want this to happen at your expense.

Here's a real-life example. Some time ago, we had some friends who knew that I was a financial planner and they wanted my opinion on something their financial planner had recommended.

Basically what this advisor was telling them was that they should take the majority of their current investments which were mutual funds, and we'll talk more about which kind of funds they should take as that is very important to the story.

In other words, they were suggesting moving their mutual fund portfolio into a more managed portfolio. As I mentioned before, I've already been around the block a few times, so I get the feeling that when they say managed, they're going to charge more.

I would advise you to be cautious of a financial planner's suggestions. If they make the suggestion of changing or putting together a portfolio using the word managed or managed, that means there is going to be a fee associated with it.

Why's that a big deal?

Having something that is managed properly isn't necessarily a bad thing, In this case, though, the clients of the advisor were investing with a mutual fund portfolio managed by American Funds.

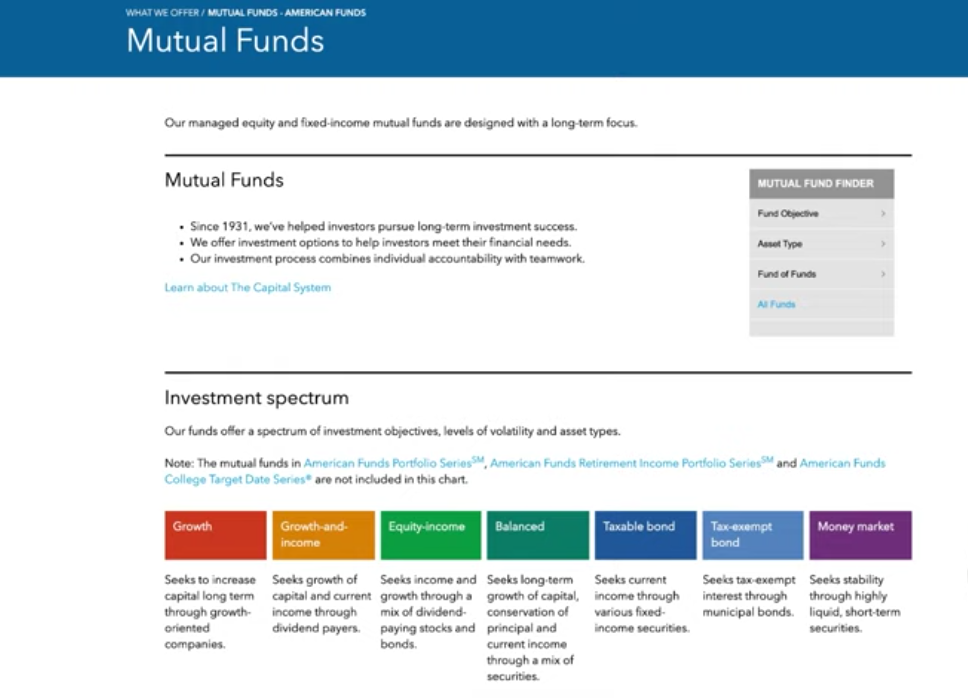

As you can see, this is just a mutual fund company. American Funds is one of several mutual fund companies that exist. So, essentially, this is like a Vanguard or a Fidelity.

It's worth mentioning that the Americans Fund family is a mutual fund company suggested by a lot of financial advisors for commissions. Not to pick on Edward Jones, for example. But anytime I looked at Edward Jones' statement from anybody, they had American Funds. They're not a bad company, just a decent one.

Why do I say that? Well, when the bear market hit in 2001 and 2002, they did well. But, fast forward to 2008 and they didn't hold up as people began selling their American Fund. But, this is what my friends had.

A Thing Called Prospectus

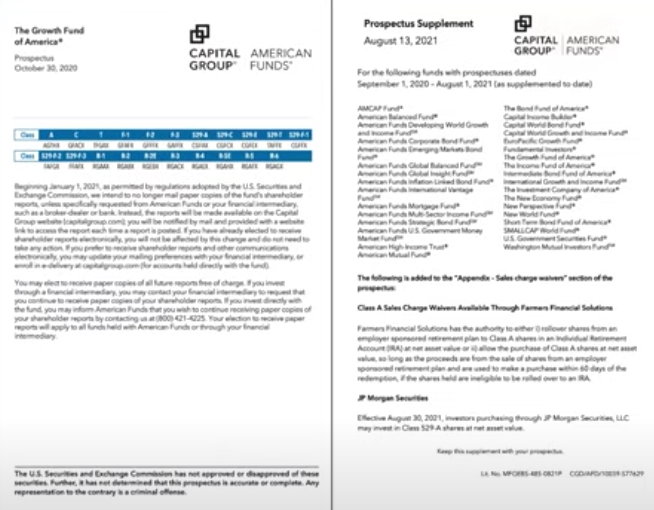

This is one of their main products, mutual funds and this is what my friends had. Now with any mutual fund that you buy, there is this thing called a prospectus.

When you buy a mutual fund or ETF you will get a little white booklet that contains everything that you have to know and don't have to worry about. They do this to prevent you from taking legal action against them if you lose money. Bottom line.

In other words, you get a prospectus. Typically, your advisor should mail you one. And then you will receive one every year or whenever there are updates.

As part of my training on how to sell mutual funds, this was one of the things that we actually used. So I guess I ought to put this out there, I am basically bashing and criticizing other people who are selling A-shares. By bashing, I mean pointing out that these are advisors who are making commissions.

To clarify, I was trained in the way I sell mutual funds and in particular, A shares, from the moment I entered the business. As a mutual fund salesman, I have always been taught to sell front-loaded funds. As part of the prospectors, the client was shown how much they should expect to pay as well as what the costs were.

The A-shares are the mutual funds where you can buy different share classes of the fund. It is common for people to buy A shares or to sell them to their clients through their financial advisors, and I'm going to share with you how it works, how much they pay, and even more specifically, how much they pay that my friends pay to purchase their A-shares from American Funds.

So let's take a closer look at a real-life prospectus.

Here's an excerpt from American Funds Capital Group's website. I assume that this is the prospectus for The Growth Fund of America — at the time this was their largest mutual fund.

I'll be honest. You don't read all 81-pages of this. It's so boring with a capital B. But for those of you who love the details and want to learn more about investing with mutual funds, this booklet can help you achieve that.

To save you some time, however, the two most important things for you to be aware of are the A and C-shares. My friends purchased A-share. This is the most common type of share class to invest in if the stock and it's usually for longer than five years.

In the prospectus, you can see that there will be a load of 5.75% of whatever you invest. You will subtract $575 from $10,000 if you have to invest. In case you're interested, the advisor gets paid 5% of the load, with the mutual fund company getting paid 0.75%. So if I sold you a mutual fund for $10,000, I would get paid 500 dollars.

How Does an Advisor Get Paid

Although you're paying now, over time you will be recouping those costs. With a C-share, you wouldn't be paying anything upfront. However, you would pay an annual fee of 1%. Since this 1% is on an ongoing basis, you'll end up paying more in the end.

However, there is an additional fee with the A-share payment. It's called the 12b-1 fee and it's the 0.25% that you pay on an ongoing basis. In addition to this, there is a management fee.

So you have management fees, distribution fees, and other expenses. So total operating expenses are 0.64, versus the 1.39 with the C-share. This is where all of these fees play into the equation.

In this case, we have an A-share, where we pay a front-end load, 5.75%, and a C share, where we do not pay anything upfront. But, then we pay a 1% ongoing fee to the advisor, in addition to management expenses.

In regards to A versus C, if you are an advisor and this is something people are saving for retirement, then the A-share seems more logical. How come? When you pay upfront instead of ongoing, it'll cost a lot more with a C-share

Also, there's another difference with mutual fund companies. Let's say that you invest more than a certain amount. So if you have less than $25,000 you will pay that 5.75 percent. Consequently, if you invest between $25,000 to $50,000 with the American Funds, then you get a discount. In that case, instead of paying a front-load of 5.75%, you'll only have to pay 5%.

Here's why this is slightly suspect.

The advisor most likely sold these A shares on the idea that the A-shares are a more cost-effective option. Again, you're paying upfront. And you're probably getting a discount for how much you are putting into the American Funds. That's going to be much less expensive than owning the C shares that have ongoing costs.

His proposal was to eliminate American Funds and switch this to a managed portfolio. However, a managed portfolio means paying a higher fee.

So, why would the advisor make this recommendation?

First, the advisor was selling his clients on the benefits of diversification. How so? Well, a portfolio consisting of mutual funds means that you would own a basket of funds. You will now have 12 to 15 different mutual funds, instead of 5 or 6.

Here's where I become really suspicious.

His next statement was, "I just don't have the time right now to manage this portfolio." But, why would he say that?

What this advisor is basically saying is that "I am too busy to manage your portfolio." As a result, I have not been managing your portfolio since I sold it.

That's a problem because now he is saying that you should switch to the managed portfolio because he doesn't have the time anymore. That's in addition to an upfront fee that's probably between 2 ½% and 3 ½% on a continuous basis. And, there are also annual management expenses, which are like 0.65% per year.

As a result, moving to a more diversified mutual fund portfolio means more management expenses.

It's because of this that this is borderline shady. The advisor must assess your management fee whenever you move to a managed portfolio? Oftentimes, you will hear about fees-based, fee-based advisors. The fees they charge are based on the assets they manage.

If they stuck with the first portfolio, they got paid upfront. After that, they got paid 0.6 and then they got paid 0.25% ongoing. But, let's say under portfolio two the advisor charges a 1% management fee. it does not include the 0.65%. So you, the client, would have to pay for the entire year 1.65% of the total portfolio value.

A 1.65% fee would be required in year two. Year three, nothing changes. And this is where the advisor is making more in the long run. Now they're making 1% instead of 0.25%.

That's a lot of math there. Long story short, though, the advisor has reached a point where they want to increase the fees they're generating on a reoccurring basis.

To be transparent, however, the advisor would have to report if they're making more money. But, maybe if you transferred firms, you might get around this.

Final Words of Advice

Even though financial advisors have to disclose this information, they can still sell their clients on diversification. Nothing wrong with having a diversified portfolio. But, in this scenario, the client paid a hefty upfront fee on their original portfolio. Then, 3 or 4 years later, the advisor suggested that they much to a more diversified portfolio. Now, there's a larger ongoing fee and everything's being managed by a third party.

So, before getting talked into this, ask the advisor what's really going on here. If they are acting fishy, consult another expert. Or, go to FINRA BrokerCheck and file a report. That sounds excessive. But, they're trying to double-dip by making a big fat commission check on the back of the front end while making more on the back end. And, that's totally not okay.

The post Keeping Your Money Safe from Shady Advisors appeared first on Due.