Mark Zuckerberg's Quest to Kill the Smartphone Could Have Some Scary Side Effects In 2016, Mark Zuckerberg revealed his ambitious 10-year plan for the company, calling his shot for a future where artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented reality and ubiquitous connectivity are all core to the social network's strategy.

This story originally appeared on Business Insider

There are really two Facebooks: One, the social network that billions of people use to share baby photos and political opinions; and two, the future factory that's building autonomous helicopters, artificial brains and metaphysical selfie sticks.

Right now, they're still treated as very separate entities. When we talk about the effects of, say, fake news stories or so-called "filter bubbles" under the Trump administration, we're really talking about that first Facebook, the social network we're familiar with and how it informs our interactions with the real world.

Maybe it's time we stopped thinking like these two different Facebooks are different companies. After all, it seems like Facebook already has.

In 2016, Mark Zuckerberg revealed his ambitious 10-year plan for the company, calling his shot for a future where artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented reality and ubiquitous connectivity are all core to the social network's strategy.

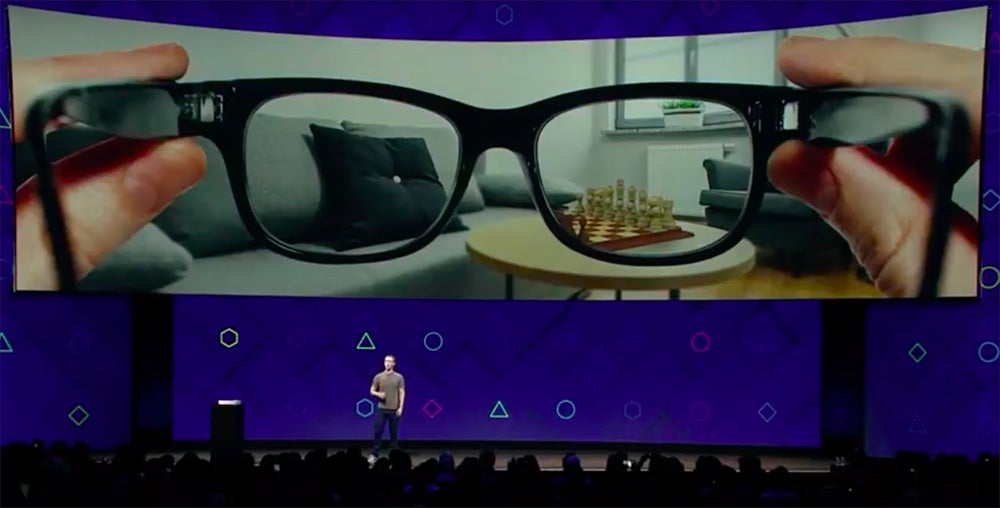

At this week's Facebook F8 conference, Zuckerberg underscored that roadmap: His vision for Facebook brings the social network closer to the real world than ever before, using your phone's camera to project digital imagery into the real world. It's another milestone on the smartphone's very slow march to the grave, and a new chance to ask questions we need to think about now, before it's too late.

Welcome to 2026

On the one hand, Facebook's vision of 2026 sounds kind of cool: As Facebook loves to point out, you'll no longer be limited to physical proximity if you want to spend time with anyone from all over the world; just meet them in virtual reality. And your McDonalds cashier could actually be an artificially-intelligent computer program, with a human-looking avatar beamed into the augmented reality glasses Facebook hopes you'll be wearing.

To Facebook, this is the natural extension of its mission to help people connect with other people -- even the potential commercial applications are to help companies talk to their customers in a more natural way, Facebook has said.

And as Zuckerberg himself noted at F8, it has the potential to replace every screen in your home, including the TV and, one day, the smartphone, as the combination of the digital and physical worlds replaces the need for an additional device. The eventual goal, he says, is for Facebook to build innocuous augmented reality glasses.

But Facebook had a lot of stumbles over the last year or so, which means this vision is worth taking a very close look at.

From the controversy over allegedly censoring conservative news sources from Facebook's trending topics, to the recent discussion over "fake news" and fact-checking in the wake of the presidential election, we're starting to explore how social media, and this company in particular, affect what we read, and perhaps what we think.

In the virtual reality world that Facebook is building, the company could actually control what we see and what we experience. Facebook's mysterious algorithms will be at work in ways we've never really experienced before, interfacing directly with our senses.

In the short term, as Buzzfeed's Nitasha Tiku points out, this is going to make it even harder to tell fantasy from reality on social media: In a world of painstakingly-staged Instagram photos, augmented reality is going to make it even easier to present a version of your life that doesn't exist. As Zuckerberg says, "you can add a second coffee mug, so it looks like you're not having breakfast alone."

If you really take it to the extreme, things could get even weirder. For instance, a Facebook glitch in November suddenly caused two million or so users, including Zuckerberg himself, to be declared dead. That's distressing when it's just on a screen. Now, as Facebook's next big bets infiltrate our daily habits, these kind of algorithm failures could have tremendous consequences.

What happens if a Facebook glitch in augmented reality causes some people to become invisible in your field of vision? What if you start seeing people who aren't there? Or an audio error accidentally means you can only communicate in Tagalog until your reset your glasses?

What if a Facebook algorithm change means that people who disagree with you are literally rendered invisible?

It's a weird, science-fictional thing to worry about, but it's increasingly a weird, science-fictional sort of world. Remember that Facebook, once thought about as a toy, is now so crucial to the dialogue that we're talking about its role in global politics. With virtual reality and augmented reality, Facebook is hoping to repeat the trick.

Facebook deserves at least a little credit here. Zuckerberg hasn't always been perfect when it comes to matters of social responsibility and giving, as evidenced by the difficulty the Newark schools had in taking full advantage of his $100 million donation. But his heart seems to be mostly in the right place, and he's definitely put his money where his mouth is with the Zuckerberg-Chan charity initiative, where he vowed to give 99 percent of his fortune to social causes. There are worse people to lead the charge into an algorithmically-defined reality.

Still, Zuckerberg won't be in control of Facebook forever. If he leaves or dies, his super-voting powers do not transfer to his heirs; the company's investors have seen to that. So, as Facebook enters the third stage of its ambitious 10-year plan, here's my fondest wish: While we argue about the role of Facebook in our lives today, I'd love for the company to really think -- and talk -- about the role it might play tomorrow.