Here’s How WeWork Pinpoints the Perfect Locations for Its Co-Working Spaces in Neighborhoods

When evaluating potential office locations in new markets, the workspace provider doesn’t just rely on luck.

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

In this series, The Fix, Entrepreneur Associate Editor Lydia Belanger shares her conversations with founders and executives whose solutions to inefficiencies can inspire others to find new ways to save themselves time, money or hassle.

Workspace provider WeWork has skyrocketed to become the leader of its industry in a matter of just seven years. The company, which rents office and desk space to teams and individuals, has 218 office locations in 53 cities worldwide, and it’s not planning to slow down anytime soon. After a $4.4 billion investment from SoftBank’s Vision Fund earlier this year, WeWork reportedly is one of the top five most valuable startups, worth $20 billion.

To keep up with demand and ensure it continues along its growth trajectory, the company is quietly building a trove of data about how its members work in order to better serve them. But to attract those members, it first has to be strategic about where its offices are. Decisions come down to more than lease length and building aesthetic, because what lies directly outside a WeWork’s motivational-poster-adorned walls is just as important as the walls themselves. WeWork members inherently value flexibility and options — after all, they choose to rent space tailored to their needs rather than commit to a lease of their own. They want certain types of amenities in close proximity — from coffee shops where they can take clients for meetings to fitness studios where they can blow off steam during their lunch break.

Related: Why This Legacy Company Is Betting on a Glass Highrise Vision of the Flexible Workspace

A dense urban environment such as Manhattan, where WeWork is headquartered and has 40 locations to date, is easy to populate, says Aaron Fritsch, head of product systems and operations at WeWork. The entire island is saturated with bars, restaurants, coffee shops and gyms. “I don’t think that there’s anywhere in Manhattan where you could put a WeWork, and it wouldn’t draw a crowd,” Fritsch says.

However, in cities that WeWork identifies as its secondary and tertiary markets — in other words, its next frontiers — it’s a bit trickier to figure out which neighborhoods to move into next. WeWork’s real estate team is less likely to be familiar with smaller cities, especially those that don’t yet have WeWork locations. And Google Maps doesn’t provide a comprehensive overview of everything that’s nearby.

“The single biggest blocker to our ability to expand is plainly and simply how many leases we can sign,” Fritsch says. He estimates that for every one lease WeWork signs, it evaluates and passes on two to five others. As WeWork aims for its growth goals, hiring more employees to its real estate team isn’t the most efficient way to help expand its footprint.

“We need a systematic and scientific way of making assessments,” he says. “Anything that we can do to give people tools to synthesize more information in less time immediately correlates to more locations open.”

The fix

Fritsch was previously director of software at Case, a consultancy that helped clients make architectural, construction and building operations decisions based on data. WeWork acquired Case in June 2015 after working with the company for three years. Throughout 2015, WeWork grew from 23 to 55 locations, and Fritsch and the former Case team were tasked with helping their new company scale even faster going forward.

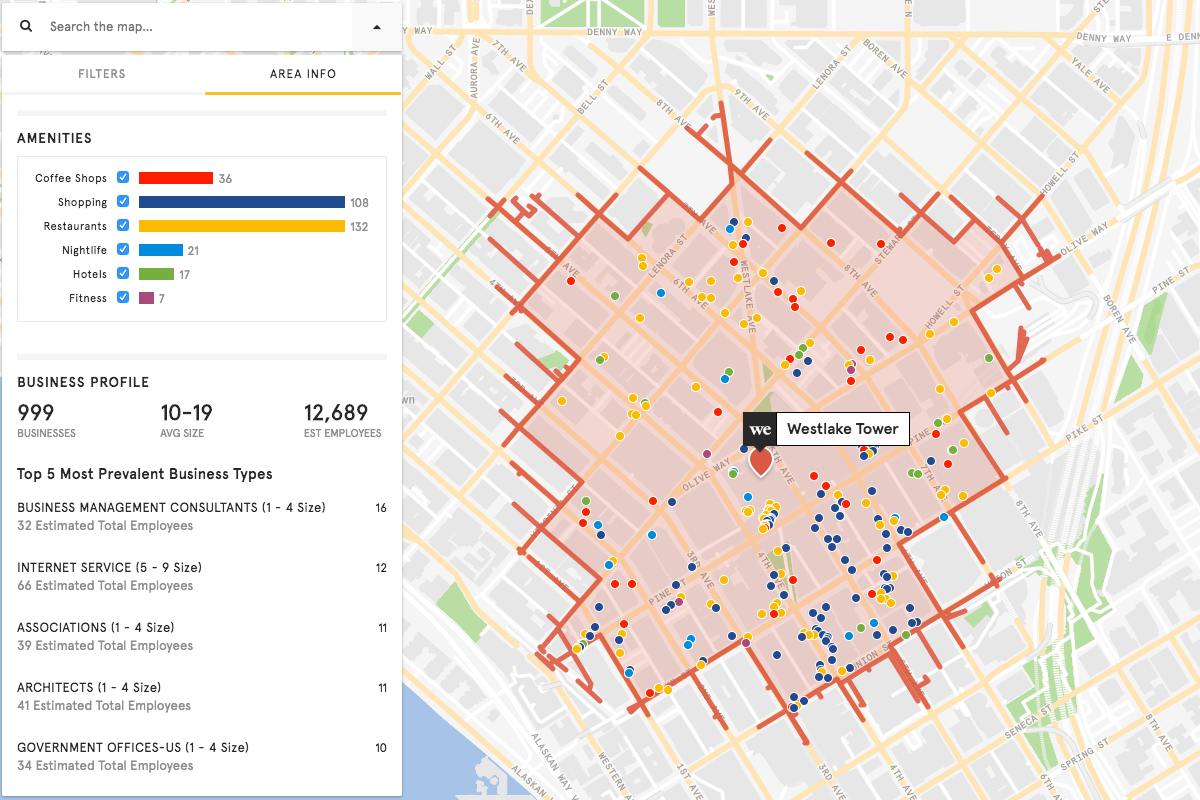

WeWork already had software that could create heat maps from geographical data, but they didn’t have a source of data about what amenities were located in a given area. It turned to Factual‘s Global Places Data, which contains more than 130 million records of places across 52 different countries, and it input the Factual data into its internal mapping software.

Fritsch and his colleagues did some data regression analysis to identify what types of amenities were near existing, thriving WeWork locations. He says they found some false positives — for example, they found a high correlation between karate studios and WeWork locations. But otherwise, he says, “it generally validated our intuition” about what amenities are most crucial.

They then color coded various relevant categories, including “coffee shops,” “restaurants,” “fitness” and “nightlife.” Now, WeWork’s real estate team can draw a radius around a given geographical location and visualize the density of each amenity type. It tells them how many cafes are nearby rather than which cafes are nearby, Fritsch clarifies.

When WeWork’s real estate group is looking at dozens of options for new buildings in cities hundreds of miles away, the data helps them narrow down their options to those they’ll actually visit when they travel to those cities. It’s just one data source WeWork uses to help with location strategy, but it’s an important starting point.

Related: WeWork Will Give Away $20 Million to Entrepreneurs to Celebrate 100,000 Members

“We’re going to look at amenities before we look at the quality of the building, because it’s a lot cheaper for us to assess amenities than it is for us to assess building quality,” Fritsch says. “It’s similar to how, when choosing a residential space, you’re going to look at what transportation options are nearby or what school district it’s in long before you’re paying an appraiser or somebody to come out and do an assessment of the foundation.”

The results

WeWork was already growing its footprint rapidly before it implemented Factual’s places data, but the company claims that its ability to assess more buildings accelerated its growth further. WeWork grew its number of locations by 95 percent between June 2016 and June 2017.

In addition to helping its real estate team evaluate potential locations, Fritsch says the Factual data platform has also been useful to its sales team. WeWork can open locations in optimal areas, but it still has to sell its product — office space — to customers or new members. The sales team can flaunt stats about the number of amenities in a given area to entice new members and fill up new locations. While the real estate group is using it to make high-stakes decisions, Fritsch says there are more salespeople looking at the data than employees on the real estate side.

While it’s been helpful across the organization, Fritsch qualifies that the data can’t do all of the work for WeWork.

“At the end of the day, relationships and an intuitive understanding of a market is incredibly important,” Fritsch says. “The point isn’t to replace our real estate group with robots. It’s to equip our real estate group with a competitive advantage to be able to identify the best locations.”

Another take

Jeff Lessard, a senior managing director on Cushman & Wakefield’s Strategic Consulting team, echoes Fritsch’s comments about data’s limitations. On paper, the data might suggest that a given market will be perfect for your business, but when you get there, you might find otherwise.

“We’re big believers in data, obviously, as consultants. We have our noses in it every day, all day,” Lessard says. “But there’s simply no substitute for looking, touching, talking to people and that gut feeling you can only get by going to the city and seeing it for yourself.”

Related: 4 Ways Co-Working Spaces Inspire Innovation and Collaboration

Just as WeWork uses data to figure out which locations to ultimately visit in person, other businesses can, too. But before companies think about purchasing a subscription to a data service, Lessard says, they should think about what data they can gather themselves. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has data on job skills and the Economic Research Institute is one of many sources of labor cost data. An even more accessible option Lessard suggests is LinkedIn, given its wealth of free public information about what’s happening in any labor market.

You should think about the needs of your new operation. Call centers, for instance, often are in suburban areas where real estate is less expensive. But nowadays, if you’re looking to attract top talent, being in a more urban area may help you attract and retain talent. A startup in growth mode, Lessard says, needs to be accessible to industry and new customers and clients, so while that might mean investing in a more expensive location.

Like WeWork, companies might also want to look at shops and bars, especially if they want to appeal to highly skilled millennials with active lifestyles.

“Cost of the real estate is dwarfed by the cost of employee churn,” Lessard says. “It’s not even close.”

Once you arrive in your city of interest, Lessard encourages meeting with community leaders, local recruiting agencies and economic development corporations to get more insights — and in some cases, data.

Disclaimer: WeWork is a Cushman & Wakefield client. Lessard, quoted above, does not consult with WeWork.

Related video: Why Your Customers Should Be Your Friends

In this series, The Fix, Entrepreneur Associate Editor Lydia Belanger shares her conversations with founders and executives whose solutions to inefficiencies can inspire others to find new ways to save themselves time, money or hassle.

Workspace provider WeWork has skyrocketed to become the leader of its industry in a matter of just seven years. The company, which rents office and desk space to teams and individuals, has 218 office locations in 53 cities worldwide, and it’s not planning to slow down anytime soon. After a $4.4 billion investment from SoftBank’s Vision Fund earlier this year, WeWork reportedly is one of the top five most valuable startups, worth $20 billion.

To keep up with demand and ensure it continues along its growth trajectory, the company is quietly building a trove of data about how its members work in order to better serve them. But to attract those members, it first has to be strategic about where its offices are. Decisions come down to more than lease length and building aesthetic, because what lies directly outside a WeWork’s motivational-poster-adorned walls is just as important as the walls themselves. WeWork members inherently value flexibility and options — after all, they choose to rent space tailored to their needs rather than commit to a lease of their own. They want certain types of amenities in close proximity — from coffee shops where they can take clients for meetings to fitness studios where they can blow off steam during their lunch break.